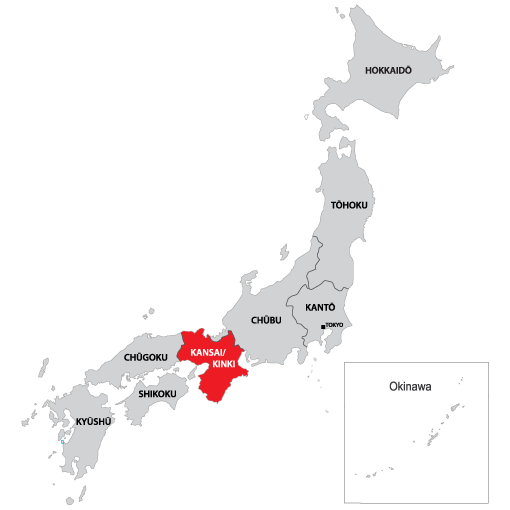

The Kansai region of Japan, lying in the West of the main Japanese island of Honshu, is considered to be the heartland of Japan’s culture and civilization.

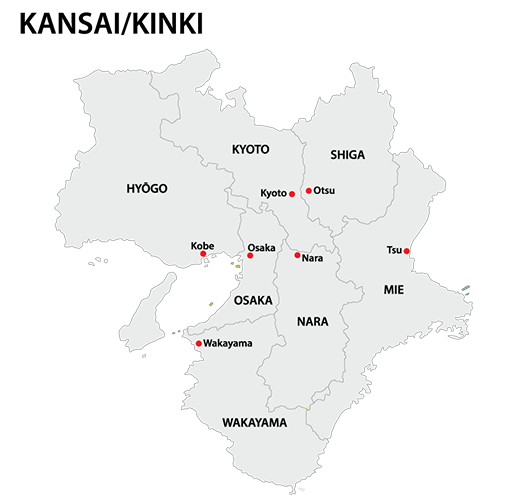

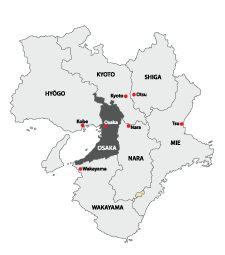

The population of the region is second only to the Kanto area. Kansai also lies at the crossroads of where spiritual, intellectual, and cultural influences entered Japan from broader Asia. Japan’s oldest ancient capitals rose in the Kansai region, and there remains a strong local identity reinforced by a strong local dialect. The region is also known as the Kinki region, which means ‘near the capital’. Kansai stretches from the Sea of Japan to the Japan Inland Sea, and the Pacific Ocean. The region is bordered to the east by the Chubu region and to the West by Chugoku. The area is home to three of Japan’s major cities: Kyoto, Osaka, and Kobe, which are collectively known as Keihanshin. Rail lines in the area take their names from this title – the Keihan line, the Hankyu line, and the Hanshin line – and several other private rail lines are found in the area. The seven prefectures that make up the region are not exclusively urban – a variety of geographies are found in the area from mountain to sea in Kyoto, Shiga, Nara, Osaka, Hyogo, Mie, and Wakayama. The names of the ancient regions established in the seventh and eighth centuries in this area are still well known and feature in place names today: Yamato, Yamashiro, Kawachi, Settsu, and Izumi. For many travelers, a stay in Japan is not complete without a visit to the Kansai region. It is hardly surprising, considering the incredible cultural legacy found in the region – over three-quarters of Japan’s ‘National Treasure’ buildings are found in Kansai, as are many UNESCO World Heritage sites, and half of the nation’s works of art considered to be ‘National Treasures’. Many of Japan’s living traditions and forms of performing arts have origins in Kansai.

Kyoto Prefecture

Kyoto was the capital of Japan for over a thousand years, until the early seventeenth century. With such an enduring position at the heart of Japan’s government, spiritual, and cultural development, Kyoto retains a rich cultural legacy that can be found throughout the prefecture. The area is not entirely urban. The modern capital sits in a basin, encircled on three sides by mountains, but once beyond the mountains and outside the city limits, the prefecture takes on a more rural feel. You need not travel far outside of Kyoto to find yourself in nature. Given Kyoto’s rich history, the city is home to several significant sites, National Treasures, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and Japanese patrimony. Entire books can be written about what the city has to offer, and many have been written. Here we describe the sites that visitors most ask us about, and which offer magnificent insights into the city and Japan overall but we can only cover a fraction of what the city has to offer and there are many more locations yet to explore!

Kyoto was the capital of Japan for over a thousand years, until the early seventeenth century. With such an enduring position at the heart of Japan’s government, spiritual, and cultural development, Kyoto retains a rich cultural legacy that can be found throughout the prefecture. The area is not entirely urban. The modern capital sits in a basin, encircled on three sides by mountains, but once beyond the mountains and outside the city limits, the prefecture takes on a more rural feel. You need not travel far outside of Kyoto to find yourself in nature. Given Kyoto’s rich history, the city is home to several significant sites, National Treasures, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, and Japanese patrimony. Entire books can be written about what the city has to offer, and many have been written. Here we describe the sites that visitors most ask us about, and which offer magnificent insights into the city and Japan overall but we can only cover a fraction of what the city has to offer and there are many more locations yet to explore!

While Kyoto station lies in the middle of the city of Kyoto, it lies at the southern end of the main central district of Kyoto. The station remains a hub of the city, servicing both commuters and visitors alike. Many shopping malls and department stores lie near the station – adjoining it, below it, and radiating out from it – and Kyoto’s branch of Isetan is directly connected to the station. There are restaurants both within the station and the shopping precincts, ranging from branches of well-respected Kyoto dining institutions to the ‘ramen koji’ or alley of ramen shops representing different styles of ramen from around Japan. The architecture of the station contrasts with Kyoto’s reputation for being a historical and traditional city, with its sweeping modern and innovative style.

Slightly North of Kyoto station, just a short walk away, are two temples that are part of the Jodo Shin sect of Buddhism – Higashi Hongan-ji and Nishi Hongan-ji. The abbots of the Hongan-ji temples did not limit themselves to the spiritual world and were a political force as well. Higashi Hongan-ji, a Buddhist Temple established in 1602 that is Kyoto’s largest wooden building. The buildings are more recent, having been destroyed by fires at various points during its history. The Shin sect of Buddhism was founded by Shinran, and his mausoleum, which has been moved many times since his death in the 1200s, is now located here. Nishi Hongan-ji, built in 1591 with the support of Tokugawa Ieyasu, lies just a few streets to the West and has some older buildings dating as far back as the 17th century, and a number of the structures in the temple precincts are National Treasures. The Temple is also a UNESCO World Heritage site. Further to the East is Shoseien, a traditional garden, and residence affiliated with Higashi Hongan-ji.

West of Nishi Honganji temple are some historic buildings and structures that were once part of Kyoto’s old pleasure and entertainment district. The Shimabara gate used to mark the entrance to a district of inns, teahouses, and drinking establishments of yore. Later as more tea houses opened up, geisha houses opened to entertain visitors, making Shimabara the oldest of the city’s Geisha districts. Today there are no current active geisha houses in the area, but the area remains associated with tayu, the highest level of geisha, associated with the Wachigaiya teahouse and okiya. The second of the two remaining teahouses in the area, Sumiya, has seasonally limited visiting hours. It is architecturally significant as it is the only ageya from the Edo period remaining in Kyoto and is the largest machiya in the city. Ageya were banqueting halls where large parties could be entertained. Sumiya was favored by the Shinsengumi and the current building bears the scars of this association. Wachigaya is still used by geisha from other districts in Kyoto and tayu to entertain and is not open to the public. Both buildings have rather plain exteriors, which conceal more artistic and well-appointed rooms inside.

For more secular entertainment near Kyoto station, visitors exiting Kyoto station will find Kyoto Tower hard to miss as it sits opposite the north side of the station. While the tower is a bit of a blot on the landscape of the city, it is a handy visual guide to help orient yourself in the downtown area. The tower provides views over the city and the recently redeveloped Kyoto Sando floors of the building below the tower contain a number of restaurants, souvenir shops, and experience spaces where you can try your hand at cooking and craft-making classes. To the west of the station is the compact Kyoto Aquarium, which features exhibits illustrating the ecosystem and fish of Kyoto’s rivers. Probably the highlight of the attractions in this area is the Kyoto Railway Museum, which features early trains right through to the sleek shinkansen of today, and hands-on exhibits that are great for families.

Heading East from Kyoto Station will also bring you to some of the interesting sights in southern Higashiyama. The Kyoto National Museum is along Shichijo street and has both a permanent collection and temporary exhibits. Those with an interest in folk art may wish to visit the home of Kawai Kanjiro, a renowned ceramic artist and supporter of the mingei craft movement in Japan. The house still has his traditional stepped ‘noborigama’ kiln. On exhibit are his works of art and mementos from his life.

The area also is home to some interesting sacred sites. Across the street from the Kyoto National Museum is the understated but powerful Sanjusangendo Temple. Inside this Tendai temple are 1001 thousand-armed statues of Kannon that shimmer delicately in the low light. The temple itself was founded in 1164 by Taira no Kiyomori, and the main building of the temple dates back to the 1200s. Another interesting site behind the Kyoto National Museum is the Toyokuni shrine, dedicated to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. When his rival Tokugawa Ieyasu rose to power, he ordered the shrine to be closed, and so it was for over 200 years and was only saved from destruction by the pleading of Nene, Toyotomi’s wife.

The Higashiyama area stretches along the Eastern mountains of Kyoto stretching across the length of the city. Most visitors to Kyoto spend a fair amount of time wandering through the historic and beautiful townscapes of southern Higashiyama. Extending mostly from Gojo Dori to Sanjo Dori, this area contains many of the beautiful streets and back lanes that people think of when they think of Kyoto.

Arguably one of the most famous temples in Higashiyama is Kiyomizu-Dera or Kiyomizu Temple. This UNESCO World Heritage Site temple sits perched above the city of Kyoto on the side of Mt. Otowa and commands impressive views over the city. The temple itself is built on a grid-like Zelkova wood platform, not unlike stilts or heavy-duty scaffolding. Given its positioning, the only way to reach the temple is to walk up and there are two main pathways you can take to reach the temple. The ascent up Gojozaka will take you past several small shops, establishments offering snacks, souvenirs, and crafts. Another route – Ninenzaka and Sannenzaka, heads towards Gion and the Nene-no-michi and Ishibei-koji, some of Kyoto’s most beautifully preserved streets. Here, the roads are lined with traditional wooden machiya buildings, temples, and pagodas, which are a delight for the eye and a photographer’s paradise. Visitors will often approach on one route, and descend another.

Kiyomizu-dera was established in the year 778 after the monk Kenshin followed a dream which led him to the clear waters coming from the mountain. These give the temple its name, which means ‘Pure Water’. Here he built a temple dedicated to merciful Kannon. Today you may drink from these same waters. There are three streams of water, each of which is said to bestow different gifts. One bestows long life, one love, and one success. You must pick one – drinking from all three fountains would be greedy and may anger the gods! If you need more help with your love life, the Jisshu shrine that sits behind the main hall of the temple offers you an opportunity to seek the assistance of the spirits.

While Kiyomizu-dera is the best-known of the temples in Kyoto, by continuing to walk along Nene-no-michi in the Higashiyama district, you will encounter some lesser-visited but no less important temples, some of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites. Kodai-ji, a Rinzai-zen temple, is a gem and well worth a visit. The temple was built by Nene, the wife of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who became its priestess following the death of her husband. The construction of the temple was funded by Tokugawa Ieyasu, and his largesse resulted in beautiful buildings, which include tea houses associated with tea master Sen no Rikyu, and a moon-viewing pavilion, as well as a mausoleum for Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Nene. The temple was established in 1606 and is well known for its gardens, designed by respected designer Kobori Enshu. The buildings are ornately decorated inside as well. In Spring and Autumn, the grounds of the temple are illuminated, making for a different means to view the temple. Across the Nene-no-michi lies Entoku-in, a sub-temple of Kodai-ji, which is small but beautiful, particularly during spring and autumn where its gardens offer seasonal views.

Continuing northward in Higashiyama eventually brings you to Yasaka shrine, a shrine that is 1350 years old, predating the founding of the city, yet remaining popular for visitors and residents today. Many of the current buildings date to the Edo period. Yasaka shrine lies at the far eastern end of Shijo-dori, and it is the home of the Gion Matsuri held in Kyoto since 869. The shrine is alternately known as the Gion Shrine. The shrine has a history of being a place of prayer for protection against plague, and indeed the Gion Matsuri is a festival originated to seek deliverance of the city from a plague. There are several smaller shrines on the grounds in the precincts where one can also entreat the kami for a successful marriage, for beauty, or success in business, or even to the wild soul of Susanoo-no-mikoto to assist you. In addition to the Gion Matsuri, the shrine has a full year of festivals, many often attended by maiko and geiko from the nearby Gion districts.

Across Higashiyama dori from Yasaka shrine and the historic sights of southern Higashiyama is the Gion district, which stretches broadly from Kennin-ji Temple in the south to the Shimbashi area in the north, east of the Kamo river. The Gion district is Kyoto’s entertainment district. In the southern part of Gion, along Hanami-koji, are traditional machiya housing exclusive teahouses and restaurants where geisha and their apprentices entertain, and which are only open to customers known to them and visitors referred by them. In the side streets fanning out from the district, the okiya where they live can also be found. Sadly, the past behaviour of tourists has led to the implementation of restrictions in the area to protect the geiko and maiko, as geisha and their apprentices are known in Kyoto. It is now forbidden to photograph along some of the smaller lanes off of Hanami-koji, and rules for correct behaviour are posted along Hanami-koji. The area is still beautiful to walk, particularly at dusk as the neighbourhood comes alive. Kennin-ji temple, at the southern end of Hanami-koji, is a head temple of Rinzai Zen and was first founded by monk Eisai in the early 1200s, making it one of the oldest Zen temples. This temple precinct provides an oasis of calm in the vibrancy of Gion.

The area of Northern Gion, in the Shimbashi-dori area, is also beautiful and atmospheric, with the gently flowing shallow waters of the Shirakawa River, small shrine, and machiya. The Tatsumi bridge is also such a beautiful and atmospheric spot that it has become popular with bridal photographers. The canal is lined by a number of exclusive restaurants. Following a section of traditional buildings, the street opens out into a more modern and conventional district of bars and nightlife establishments.

Returning to Higashiyama and the area east of Higashiyama-dori, just north of Yasaka shrine, is Chion-in. The temple’s entrance is marked by the massively impressive Sanmon gate. Chion-in is the head Jodo, or Pure Land Buddhist temple in Japan. Founded by Honen, the temple’s gate is Japan’s largest, and its bell is Japan’s largest. Setting the superlatives aside, the Jodo sect sees salvation as something that is possible for all. The buildings of the temple are worth a visit. The Miedo hall is dedicated to Honen, founder of Jodo Buddhism, and the Amidado Hall is dedicated to the Amida Buddha, the lynchpin figure of the Jodo sect and the means for reaching salvation. You may wish to seek out the 7 mysteries that can be found at the temple.

Northern Higashiyama also contains a number of Kyoto’s best-loved sites and locations of interest. North of Chion-in is the Okazaki district. The area is known for being home to a number of the city’s notable museums, Heian Jingu, the City Zoo, and the Murin-an Garden.

The approach to Heian Jingu, a road that travels under a large vermillion torii gate, is the site of the primary museums in the area. Around these are the waterways of the Lake Biwa Canal, which was a prime commercial waterway between Kyoto and Lake Biwa; The National Museum of Modern Art, or MoMAK, features a modest rotating permanent collection of Japanese and international works and also hosts a number of visiting exhibitions. Its Japanese works do include Kansai and Kyoto artists. Across the street is the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art. The museum reopened in 2020 after an extensive and much-awaited renovation. The Museum houses the city’s collection of art, and while it does have a strong focus on Japanese artists overall, it is known for hosting touring international exhibitions, and for also being a focal point for Kyoto’s artists with its competitions and local art prizes. In the nearby Miyako Messe Conference Hall, the Kyoto Museum of Crafts and Design, or Fureaikan, offers an overview of the many traditional crafts pursued in the city from past to present with local pride. The museum often has local craftspeople allowing visitors an opportunity to see them at work and engaged in their craft.

At the end of the promenade, is Heian Jingu or Heian Shrine. The shrine commemorates the Heian period of the city, and the city’s first and last Emperors, but was built in the late 1800s to celebrate the city’s 1100th birthday. The shrine sits around a spacious courtyard. Behind, a beautiful and extensive series of four landscape gardens provide a popular place to view both cherry blossoms and autumn foliage. The shrine’s building is a slightly reduced scale model of the ancient administrative buildings of the Emperors from the city’s Heian era history. This is somewhat unique for a shrine as it does not have a foundation in more usual sacred architecture, with the exception of its vermilion colour. The shrine was a way for the city to celebrate its pride once the capital was moved to Tokyo in the 1800’s. The Jidai Matsuri, one of Kyoto’s famed festivals which features a parade of people in historical dress, takes place here.

A number of important sites, as well as family entertainments, can be found East of the Okazaki district. On the south side of the Canal, to the east of the museums, is Murin-an garden, a small garden with an interesting history. This small, often missed garden is the villa garden of Yamagata Aritomo, a statesman of note in the Meiji and Taisho eras. The buildings and grounds are a reflection of the time, with a mix of Japanese and Western influences.

Continuing further east, heading for the mountains, brings you to Nanzen-ji, one of Japan’s top Zen temples. It is the head temple for Rinzai Zen Buddhism. Your arrival is met by the impressive Sanmon gate, built by the Tokugawa clan. It is possible to climb up to the second level of the gate to be able to look out over the full temple grounds The temple precinct is very large, with a number of sub-temples and associated temples, each of which has its admission fees and is worth a visit. In addition to being a significant Zen temple, Nanzen-ji is famed for its Hojo Garden, in the building that was once the head priest’s residence. This dry stone garden was designed by the eminent garden designer, Kobori Enshu. The temple was founded in 1291 and was originally the residence of Emperor Kameyama. Somewhat incongruously, you’ll also find a brick aqueduct that is a beloved location for photographers. The aqueduct still has a role to play in bringing water to Kyoto from Lake Biwa.

The Philosopher’s Pathway or Tetsugaku-no-michi stretches from Nanzenji. This pathway offers a lovely 30-minute walk through a quiet residential neighbourhood and along a quiet canal. The canal is lined by cherry trees, making it very popular in spring, and in autumn maples provide brilliant foliage, but the walk is attractive and pleasant year-round. On the mountainside of the walk, you pass several smaller temples that many visitors miss, such as Eikan-do, and Honen-in. The pathway takes its name from one of Japan’s greatest philosophers, Kyoto University Professor Nishida Kitano, who used to walk this route daily. The pathway ends at Ginkaku-ji, the Silver Pavilion, known formally as Jisho-ji. This temple does not have its planned sliver leaf coating but does offer beautiful gardens and grounds that make use of the hillside above the temple. Within the garden is a stone mound representing Mount Fuji. The temple was built in 1482 and was once the retirement villa of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. Ginkaku-ji became a center of Higashiyama culture, which went on to influence the entire nation with gardens, architecture, Noh theatre, the tea ceremony, ikebana, garden design, and poetry. The temple is very popular and a visit right after its opening or just before its closure will help you to beat the crowds and still enjoy this beautiful location.

Turning to the central area of the city, here you will also find several of Kyoto’s significant sites, as well as the business and commercial hubs of Kyoto. This central core is bordered to the south by Gojo dori and to the north by Imadegawa dori, and from the Kamo River in the East to the Nishioji dori in the west. At Gojo, the Kiyamachi dori, leading along the Takase river from Gojo north to Sanjoy and beyond, is lined with restaurants catering to all types of cuisine. From Shijo, visitors may want to travel one street east to delve into the Pontocho district – known for its nightlife, for being home to one of Kyoto’s five main communities of Geisha, and for dining – from casual for formal.

The central shopping areas, where visitors will find department stores such as Takashimaya, Daimaru, and Tokyu Hands, souvenir shops, and many dining options, cluster in the areas between Shijo dori and Sanjo dori, bordered to the East by the Kamo river, and to the West by Karasuma street. The Mina, Opa, and Bal complexes contain several stores within. Here, the sidewalks are covered, and some streets have been covered to create a network of all-weather shopping arcades offering everything both locals and visitors might need. Teramachi dori and Shinkyogoku dori stretch from Shijo to Sanjo and also offer movie cinemas, restaurants, and hotels. Behind the shopping, streets are many temples hidden away in causeways beyond. The city’s famous Nishiki market, a food lover’s paradise, extends west from Teramachi dori for 400 meters of the best delicacies that Kyoto has to offer. This area also is a transportation hub for the city, where bus connections can be made in all directions. The Hankyu rail terminal can be found at the corner of Shijo and Kawaramachi dori.

Just north of Sanjo dori and a few streets west of Karasuma, the Museum of Kyoto provides insights into the history of the city. Following Karasuma dori north just a bit beyond Oike dori, manga fans will find the Kyoto International Manga Museum. The museum has exhibits on manga and a large collection of titles that are eagerly read by visitors. There are some hands-on areas for children and there are demonstrations of kamishibai, a form of storytelling with pictures that had its origins in monk’s morality tales, but which in the 20th century became a popular form of street entertainment.

In the downtown core of the city, we also see the vestiges of the power structures in the city. Nijo Castle, which looks more palatial than defensive, was the power center for Japan’s shoguns, who rose to power in the Edo period. The castle is built in the Momoyama style and was built by Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first of Japan’s shoguns. The beautiful interiors of the Ninomaru palace including screen paintings by well-known artists of the time, and gold leaf decoration, rivaled the refinement of Imperial Palaces, The placement of the castle, so close to the Imperial Palace, was thought to have been a deliberate choice to emphasize the growing power of the Shogun relative to the Imperial Court, as much as it was for the Shoguns to be close to the court they were protecting. The gardens of this UNESCO World Heritage Site are worthy of time and a stroll to appreciate their beauty. The nightingale floors, that ‘sing’ to alert intruders, are a unique feature of the Ninomaru. The Honmaru building was destroyed by fire in the 1700s but its stone foundations remain and give an indication of how imposing the original building must have been.

North and East of Nijo Castle lies the Kyoto Imperial Palace. It was from here that Japan’s Emperors ruled until the capital of Japan was moved to Tokyo in 1868. It is possible to tour the grounds of the castle and view the buildings from the outside, but entry into the buildings is not allowed. The Seiryo-den and Kogosho are reminiscent of the past and are built in historic style but the current palace buildings date from 1855, rather newer than the long history of the imperial rule would imply. Numerous fires took their toll over the years. The Shishiden building was where Emperors were once installed. The Kyoto Imperial Palace is protected by high stout walls. The Sento Palace, just to the south and east of the main palace buildings but within the same large complex, was once the home of former Emperors. While the palace itself was destroyed by fire, its pleasant gardens remain.

The park surrounding the palace is vast and pleasant and is a playground for Kyotoites. The park is particularly popular during the cherry blossom and autumn seasons. These grounds once contained the residences of members of the Imperial Court, but these were destroyed when the capital was moved to Tokyo. T

To the west of the Imperial Palace, lie some sites that may be interesting for visitors with a passion for pottery or traditional Kyoto textiles. The Raku Museum is a small museum containing the simple tea ceremony pottery style handed down through 15 generations in the Raku family. The simple pottery style had its roots in Ming dynasty pottery from Henan, but then emerged into a personal style that had a simplicity and wabi-sabi style in the tradition of tea master Sen no Rikyu, and the pottery style bears a simple elegance suitable for tea ceremonies with their celebration for the irregular but well-formed tea bowls. This pottery tradition has been passed along through 450 years and Raku ware is still highly regarded today.

Also to the West of the Kyoto Imperial Palace is the Nishijin textile-making area. The Nishijin style of woven brocade is a Kyoto specialty. The Orinasu-kan provides some great insights into the production of this style of textile in a thoughtful way. Edo period Noh theater costumes are currently being restored at Orinasu-kan, and are on display, as are many other kimonos. A more commercial presentation of this style can be found in the Nishijin Textile Center.

Aside from a select few sites, the area of Kyoto North of the Imperial Palace is often missed by visitors. The area contains some hidden gems that provide insights into the history of the city and its character. The best-known sites to visitors are the cluster of Zen temples located in the Northwest of the city – Kinkaku-ji, the golden pavilion with a gold leaf exterior that doesn’t fail to make an impression, Ryoan-ji, one of the preeminent Zen temples in Kyoto famed for its dry-stone garden. Both are UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Kinkaku-ji, whose formal name is Rokuon-ji was originally the retirement villa of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (grandfather of Ashikaga Yoshimasa who was inspired by the building to create Ginkaku-ji). Just as Ginkaku-ji became the center of Higashiyama culture, Kinkaku-ji had been the center of Kitayama culture. The Emperor entertained delegates from Ming dynasty China here, and a number of cultural traditions made their way from Ming dynasty China through this entry point. After his death in 1408, and per his wishes, the residence was turned into a Rinzai Zen temple. It is so famous for the upper two floors of the building, covered in gold leaf, that it is known more commonly as the Golden Pavilion. The current building does not date to the original founding of the temple as it had perished in fire twice before -most recently in the 1950s. The interior of the building is closed to the public but contains statues of Buddha and Yoshimitsu. The grounds of the temple climb the hillside behind the temple to the Sekkatei Teahouse which was built in the Edo era. Kinkaku-ji is one of the iconic sites of Kyoto and is popular year-round.

Nearby Ryoan-ji began its life as a villa for the powerful Fujiwara family and was converted to a temple in 1450 when the abbot of Myoshin-ji, Giten Gensho, undertook the transformation. The temple’s Kyoyochi Pond was popular with nobles, as well as Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The garden was originally thought to have been laid out in the Muroyama period from the 1400s. The garden has 15 stones placed within the garden, each with a different shape. Their meaning and significance have been hotly contested over the years, and there are a number of competing theories. The designer of the garden is also unknown. A name, which can only be partially made out, is carved on the back of one of the stones, but the association of this name with the garden remains unresolved. What is known is that it is not possible to view all 15 stones at once. No matter what vantage point you view the garden from, at least one remains impossible to see.

In the area where the Kamo river and the Takano river forks in Northern Kyoto, there are two significant shrines, which pre-date the founding of the city. Kamigamo Shrine, whose formal name is Kamo-wake-ikazuchi shrine, is the first of the two Kamo shrines. Worship has taken place at this location since prehistoric times and even before the purported founding date, the shrine was associated with one of Kyoto’s most significant festivals, the Aoi Festival, which began in 544, and was associated with mountain worship from 678, but as the shrine is the protector of the city, it is often also said to have been founded at the same time of the ancient capital of Heian-kyo, or 794. Here thunder god Wakeikazuchi is enshrined.

Shimogamo Shrine, formally known as Kamo-mioya shrine, is located just north of the fork in the river. The shrine is located in the Tadasu no Mori, the forest of truth, 3.5 km south of Kamigamo shrine. Kamotaketsunomi-no-mikoto, the protector spirit of Kyoto, is enshrined here. Archaeological finds from the Yayoi period in the Tadasu no mori show that worship has taken place here for 2000 years, even though the first shrine buildings only appeared in 7th century. Shimogamo shrine is also associated with the Aoi Festival, and the festival procession travels between these two shrines. Both Kamigamo and Shimogamo shrine are UNESCO World Heritage sites, and they offer some interesting insights into the city and the believe systems of Japan.

Kitano Tenmangu shrine is another of the city’s most famous shrines. Built in the year 947, it is a popular stop for students seeking success with their exams. Kitano Tenmangu enshrines the revered Heian era scholar, Sugawara no Michizane, and those seeking to succeed in exams or gain entrance to their preferred university often come here to ask for some spiritual support. During his lifetime, the scholar was exiled to Kyushu and to ease his spirit and put an end to disasters in his native Kyoto, he was enshrined as Tenjin, the kami or spirit of education, and it is now the head shrine of 12,000 of Tenjin worship sites. Tenjin is associated with the ox, and you’ll see sculptures of ox around the expansive shrine precincts, which students may rub for luck and the gift of knowledge. The shrine is also famous for its plum blossoms, which herald the spring season, and have a festival welcoming their arrival. Hundreds of maple trees in the shrine precincts make it a popular place in the autumn foliage season. The shrine’s monthly flea market is popular with locals and visitors year round. On the doorstep of the shrine is the Kamishichiken district, Kyoto’s oldest hanamachi, or geisha district.

With Kyoto’s history as a political and spiritual center of Japan, it is not surprising that there are also a number of significant temple complexes in the city. Daitoku-ji temple is the head temple of the Rinzai Zen sect of Buddhism. The temple was established in 1319 by Shuho Myocho, and is also strongly associated with the father of the tea ceremony, Sen no Rikyu, a monk who lived and died here. Daitoku-ji is a large complex of a number of sub temples and towers and gates. Many of these remain closed to the public on a day to day basis, but during certain times of the year, special admission is granted to allow visitors to view the beautiful gardens and buildings within. Over the history of the temple has been embroiled in political conflict, was burned down in the Onin Wars in the 15th century, and then gained political support from the 16th century, allowing the temple to grow in influence and importance.

Within the Rinzai Zen sect of Buddhism is the Myoshin-ji strand, whose main temple is the Myoshin-ji temple complex in Kyoto, founded in 1337. This vast temple area consists of a number of smaller sub-temples, most of which are closed to the public. It is possible to visit a select few buildings for some insights into this temple. The grounds of Myoshin-ji were once and Imperial villa of Emperor Hanazono, who converted them to a temple. He then gifted the temple on his death to Kanzan Egen, the first abbot of Myoshin-ji to grow the complex. As with Daitoku-ji, the complex was destroyed in the Onin wars and was subsequently rebuilt. It is worth taking the tour in Japanese to see the Unryuzu dragon painting on the ceiling of the Hatto, or lecture hall, painted by Edo painter Kano Tan’yu. Taizo-in, with its beautiful gardens, and Keishun-in are two sub-temples in the complex that regularly welcome visitors.

Ninna-ji, located near Kinkaku-ji and Ryoan-ji, is also as UNESCO World Heritage recognized temple. The temple is the head temple for the Omura sect of Shingon Buddhism. Founded in 888 by Emperor Uda, who became the temple’s first abbot, it had long been associated with the Imperial family and had started its history as the Monsekiji, a residence for members of the imperial family who left the political world to enter religious life. Uda is said to have been a direct student of Kobo Daishi and there are artifacts relating to Kobo Daishi in the temple’s treasure house museum. The temple is popular during cherry blossom season for its mix of Somei Yoshino cherry trees, weeping cherry trees, and the later-blooming Omura cherry trees. The temple was also destroyed in the Onin wars and was later rebuilt. Outside the cherry blossom season, the temple complex received far fewer visitors and offers a tranquil area for strolling and contemplation.

Outside of Kyoto, but an easy jaunt from the city, are Kurama and Kibune. Each of these valley towns can be visited separately, but there is a hiking trail between the two locations, making it possible to visit both on a lovely walk of about 2-3 hours. Traditionally walkers begin at Kurama shrine, before walking up over the mountain pass and into the land of the tengu, spirits depicted with long noses, who guard over the mountain. It is said that the area between Kurama and Kibune are where the samurai Minamoto Yoshitsune was trained by tengu to be a skilled swordsman. Kurama is the birthplace of reiki,a method of energy healing, and is also well known for its onsen. Following the walk, you arrive at Kifune shrine, dedicated to the kami of water. In the summertime, Kibune offers the possibility of dining on platforms set over the river, kawadoko, which are thought to offer a cooling sensation in the summer heat. For those with an interest in Japan’s ‘power spots’, points along this route are thought to be amongst them.

The Sagano/Arashiyama district in Western Kyoto city has the feel of its position at the edge of the city limits. On crossing the landmark Togetsukyo bridge and heading toward the Arashiyama mountains, one enters the Sagano area. There has been a bridge on this site since the Heian period, and it leads visitors north to the many sights of the area. While it is not the only stand of bamboo in Kyoto, the bamboo grove here is probably the city’s most famous. The towering green shoots attract visitors year-round.

The bamboo grove abuts Tenryu-ji Temple – one of Kyoto’s preeminent Zen temples – also a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Tenryu-ji’s gardens are well renowned, as is its art. There are several other unique temples in Arashiyama. Daikaku-ji was once an Imperial villa and became a Shingon Buddhist temple in 876. Today it remains a centre for the study of the Heart Sutra and is the headquarters of Saga ikebana. Gio-ji is known for its moss-covered grounds, making it an alternative moss garden to Saijo-ji. Adashino Nenbutsu-ji gathers together 8000 grave markers of those who made the pilgrimage to Mt. Atago and never survived. The graves are gathered here and tended by the priests. Nisonin temple was once a syncretic temple representing many sects of Buddhism, though now it is Tendai. It is known for its two Buddhist statues and for being the final resting place of former Emperors and members of the imperial court. A more recent addition to Arashiyama is the modern Otagi Nenbutsu-ji, which includes many charming statues of the temple’s supporters.

For a more secular experience of the area, Okochi Sanso, the former villa of a historic Japanese movie star, offers beautiful strolling gardens. The Toriinomoto area of Arashiyama contains preserved streets, many of which have been turned into small boutiques selling local handicrafts.

South of the Sagano area, in southwestern Kyoto, are several lesser-explored sites. Immediately south of Sagano is Kegon-ji Temple, also called the Suzumushi or cricket temple. Here crickets chirp throughout the year. Further south is Saiho-ji, a temple well known for its moss gardens. It is so well known for its blanket of moss that the temple is also known as Koke-dera or the moss temple. Those wishing to visit the gardens must apply by postcard 3 months in advance, pay a steep entry fee, and engage in a devotional activity before visiting the garden. Entry is by a lottery system and not all who apply are accepted. If you are not successful, Gio-ji temple also offers lovely moss grounds, though perhaps with fewer varieties of moss than Saiho-ji. Probably the most beautiful time to visit the gardens is in autumn when the changing colours of the leaves to reds, oranges, and yellows contrast with the rich deep green of the moss below; while others prefer June when the moss is lush and green.

Those with an interest in gardens may also wish to visit the Katsura Imperial Villa. The Villa itself is not open to the public, but the gardens and grounds offer an excellent example of a strolling garden. Dotted with teahouses and small pavilions, from which the gardens were appreciated by the Imperial family. The grounds can only be visited on a tour, which must be booked in advance via the Imperial Household Agency.

The area of Kyoto city, south of Kyoto station, has some interesting sights. To-ji Temple and Tofuku-ji Temple are UNESCO World Heritage sites lying in the south and southeast of the city centre. To-ji Temple is very old indeed, founded in 796. This Shingon Buddhist temple is one of the earliest in the city, having been founded just two years after Kyoto became the capital. It has associations with the historical figure Kobo Daishi, or Kukai, who spent time as the head priest of the temple. To-ji’s pagoda dates from the Edo period and is the tallest wooden tower in Japan. It is said that the relatively low height profile of the buildings in Kyoto are due to a general understanding that the buildings of the city should not be taller than the pagoda at To-ji temple. There are some structures that are higher, but these are few.

Tofuku-ji, a Zen Buddhist temple in southern Higashiyama, is famed for its autumn foliage. Admission to the Tsuten-kyo bridge, a favourite foliage viewing spot, is extremely popular in November. On the grounds of the temple are a number of maples that turn a glorious colour with the change of the season. During the rest of the year, a number of the sub-temples of the complex offer interesting gardens, including both dry stone, and moss and stone types. Also a UNESCO World Heritage temple, Tofuku-ji has a history stretching back into the 1200s.

Fushimi, in the Southeast of the downtown core, is famous for Fushimi Inari Shrine, with its hundreds of vermilion torii gates that snake their way up the mountain and are so packed together they create a near tunnel toward the upper shrine. The shrine has a long history, predating the establishment of Kyoto as a capital. Inari, the kami that often takes the form of a fox, is associated with rice. Near the shrine, you’ll find vendors of inari sushi – slightly sweet rice packed into a fried tofu pouch – and rice crackers bearing the image of a fox. Many of the large torii gates were dedicated by sake brewers, and this area is well known for sake production. A stroll through the Western area of the Fushimi district, near the Horikawa canal, takes you into the main sake producing area of the city. Gekkeikan, one of Japan’s best-known sake brewers, offers a sake museum and insights into how sake is brewed. For a small fee, you can also sample their sakes.

Uji, in southern Kyoto prefecture, is home to Byodo-in, a UNESCO World Heritage temple originally founded in 998 that appears on the 10 yen coin in Japan. The Temple’s Phoenix Hall is beautiful, and the surrounding garden is one of the few extant examples of a Pure Land garden. The treasury of the temple contains some quite beautifully carved artifacts. Several chapters of the classical Japanese work, The Tale of Genji, take place in Uji, and there is a museum locally dedicated to the work.

Uji may be a commuter belt town for many who work in Kyoto, but it is also famed globally for its production of green tea, and particularly of matcha, despite only a small percentage of all the green tea on sale coming from this small area of Kyoto. The ubiquitous matcha found in sweets and tearooms in Kyoto will often come from Uji, or perhaps nearby Wazuka, or Minamayamshiro, areas also known for their tea production. The sloping hillsides of tea bushes in the Doshenbo and Ishitera tea fields are particularly scenic. The geographies of both areas are well suited for the growth of tea. Throughout Uji, you’ll find several tea vendors and places where you can consume tea. The Tusen Chaya teahouse is famous, built in 1160, and it is thought to have served tea to several historical Japanese figures. While the current building dates to the 1600s, it carries the patina of its centuries of operation.

For those who prefer whiskey to sake, a visit to the Suntory Yamazaki Distillery in Yamazaki will bring you to the distillery of one of Japan’s best-known brands. After booking in advance, visitors can visit the distillery’s museum and tour the facility.

For a taste of the countryside within the city limits of Kyoto, Ohara is a town nestled in the mountains in the North of the city. The main draw for local visitors is Saizen-in Temple, founded by Saicho, the originator of the Tendai sect of Buddhism, in the eighth century. Sanzen-in is one of five Monzeki temples – temples where Imperial family members served as head priests. As is the norm in Japan, the route to the temple is lined with shops and restaurants that cater to the needs of visitors. There are several smaller temples around Saizenin – Shoren-in, Hosen-in, Jikko-in, Jorengei-in, and Raigo-in – also of the Tendai sect. Behind the main temple in the forest is the Otonashi waterfall.

Miyama is a beautiful village of preserved kayabuki, or thatched-roof cottages, located roughly 50 km north of Kyoto city in Kyoto Prefecture. The vast majority of the kayabuki are private residences, and the village is a living village but does offer some small restaurants that cater to visitors that come for this taste of traditional Japan. At the end of the town is the entrance to the Ashiu forest, a pristine forest that can only be entered with a guide as it is home to rare plants and is a habitat for wild monkeys, bears, and deer. The land here is owned and stewarded by the University of Kyoto.

Amanohashidate lies in the area known as ‘Kyoto by the Sea’. In a nation that loves to rank views, Amanohashidate is said to be one of the top three views of Japan. This 3.3 km sandbar stretches across Miyazu Bay is covered by evergreens, and at its end, the picturesque Motoise Kono shrine is located. The unique geographic attributes of this area were surely a home to powerful kami, and the name Amanohashidate means ‘bridge to heaven, and was the route that founding god Izanagi took from heaven to reach Izanami. It’s easy to see how it was perceived as such. The sandbar can be traveled on foot or by bicycle. Nearby, some more modern attractions, including an amusement park, have been built on the hillsides overlooking this popular destination.

The small fishing village of Ine lies in the very north of Kyoto prefecture on the Tango Peninsula and is famous for its funaya. These buildings combine fishermen’s residences with boathouses that open out directly onto the bay. There are several ways to see the funaya. The best way to view them is through a cruise on the bay, which will allow you to see the funaya from the perspective of the fishermen that live there, as these are private homes for many villagers. For those who wish to take a do-it-yourself approach to get a seaside view, there are also sea kayaking options on the bay. Some of the over 200 funaya have been converted into accommodations accepting guests, making it possible to see the inside of a funaya and experience a stay perched above the water.

Osaka Prefecture

Osaka Prefecture is a powerhouse. It is the second smallest prefecture in Japan in terms of landmass, but in terms of population, the prefecture is the second most populous in Japan and is home to no less than 7% of the country’s people. Much of this population clusters in and around the large city and conurbation of Osaka, making it a vibrant and lively city, often included as one of the ‘must-visit’ places on urban travelers’ itineraries for Japan. As far as ‘second cities’ go, everything seems brighter, flashier, and noisier in this city with a real joie de vivre. While Kyoto is a city of history and old imperial and military influences, Osaka has a long history as a port city and was once known as Naniwa. Naniwa served as the earliest capital of Japan when they still moved to the palace of the prevailing emperor. Osaka has in modern times emerged as the commercial and business heart of Japan. Osaka Prefecture is bordered to the Northwest and West by Hyogo Prefecture, to the North and northeast by Kyoto, to the East by Nara, and to the South by Wakayama. It sits squarely in the heart of Kansai. Osaka Bay sits to the Southwest. The city is characterized by a series of canals and rivers that travel through the city, allowing for the movement of goods to and from the port.

Osaka Prefecture is a powerhouse. It is the second smallest prefecture in Japan in terms of landmass, but in terms of population, the prefecture is the second most populous in Japan and is home to no less than 7% of the country’s people. Much of this population clusters in and around the large city and conurbation of Osaka, making it a vibrant and lively city, often included as one of the ‘must-visit’ places on urban travelers’ itineraries for Japan. As far as ‘second cities’ go, everything seems brighter, flashier, and noisier in this city with a real joie de vivre. While Kyoto is a city of history and old imperial and military influences, Osaka has a long history as a port city and was once known as Naniwa. Naniwa served as the earliest capital of Japan when they still moved to the palace of the prevailing emperor. Osaka has in modern times emerged as the commercial and business heart of Japan. Osaka Prefecture is bordered to the Northwest and West by Hyogo Prefecture, to the North and northeast by Kyoto, to the East by Nara, and to the South by Wakayama. It sits squarely in the heart of Kansai. Osaka Bay sits to the Southwest. The city is characterized by a series of canals and rivers that travel through the city, allowing for the movement of goods to and from the port.

Osaka is also one of the main international air gateways for Japan, with two airports in the Prefecture. Kansai International Airport was built on reclaimed land in Osaka Bay and sits south of the city. When arriving at Kansai Airport, you can travel onward to Osaka by two trail lines departing from the Kansai International Airport train station which connects to the airport. There is also limousine bus service to the city. There are a limited number of domestic services that arrive at Kansai International Airport. Most international air traffic arrives at Kansai Airport. Osaka International Airport, also known as Itami, is the primary domestic airport for Osaka. Itami is connected to central Osaka by limousine buses and Osaka’s monorail system. When traveling from Tokyo, the simplest way to travel is by bullet train, as the total travel time from the city centre to city centre is shorter.

The northeast of Osaka prefecture consists largely of commuter towns where the workers of Kyoto and Osaka raise their families. There are smaller parks, temples and shrines, and shopping malls in this area. When traveling between the cities, you may see some of the major Japanese companies with a presence in the area – Meiji chocolate, Yamazaki Whiskey, Nintendo, and more. Ikeda lies in the north of Osaka Prefecture. For those seeking a different way to explore Japanese cuisine, and one of its biggest food exports, the cup noodle museum offers an interesting way to spend a morning or afternoon. Visitors learn about the rise of instant ramen, a convenience food that is now consumed far and wide outside Japan and even have a chance to make a personalized ramen, complete with their own decorated cup.Takarazuka is another spot in Northern Osaka well known to the Japanese – primarily for its all-female troupe of dramatic performers. While in classical Kabuki, men play both men and women’s roles, in an about-face, the Takarazuka Revue has women playing both men and women’s roles.

The northern part of Osaka prefecture is also a good location to seek out greenery and peaceful parks. In 1970, the World Expo came to Osaka. The former exposition grounds were turned into a large 264-hectare public park complex, with museums, and play areas. Thousands of cherry trees are planted in the park, making it popular in springtime, but it is equally beautiful in the autumn foliage season. Taro Okamoto’s iconic ‘Tower of the Sun’, a landmark of the Expo, still sits within the grounds of the park, and it is now home to the well-regarded National Museum of Ethnology and the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. For those seeking to unwind after some time in the city, the Japanese gardens within the park offer a tranquil respite.

Minoo Park offers another tranquil area to escape the buzz of the city. Lying just north of Osaka, the park is largely forested, making it a wonderful location to view the changing autumn foliage in late November as the trees on the mountains shift to beautiful crimson, yellow, and orange hues. The momiji, or autumn maple leaves, are even served in tempura here, so in addition to appreciating the view with your sense of sight, you can enjoy them with your senses of smell and taste. The popular ‘centerpiece’ of the park for day visitors from the city is the 3km route to its waterfall. The route is lined with quaint shops and eateries. Halfway along the route to the waterfall lies Ryuan-ji Temple, a focal point of Shugendo activity in the area. In addition to the gentle walk to the waterfall, there are other more challenging hikes in the mountains. Deeper in the park is Katsuo-ji Temple. For 1300 years, visitors, including Emperors and Lords, have come to pray for luck or victory in their endeavors. As a testament to their success, many leave daruma with both eyes filled, indicating a wish granted.

The Northern area of the city of Osaka is its newer modern heart and has developed in recent years as a transportation hub. Visitors arriving by shinkansen, or bullet train, arrive at Shin-Osaka station, built specifically to accommodate the fastest train route and service both the Tokaido (Tokyo to Shin-Osaka) and San’yo (Shin-Osaka to Hakata) shinkansen routes. The station’s various floors offer restaurants, convenience stores, drugstores, and other shops that serve the needs of both business and leisure travelers. The Haruka line, which connects Kansai International Airport to the bullet train line and Kyoto, stops here also.

The city’s other main station, Osaka station, is a short subway journey away, south of the city’s Yodo River. Osaka station service Limited Express, Express, and local rail routes. It lies at the center of the Umeda district of Osaka. Having recently finished an extensive redevelopment project to improve the station, it is now at the heart of a modern complex of multi-use developments of shopping, office blocks, hotels, and entertainment. The surrounding complex is so large it has been named Osaka Station City, and it is nearly a city in and of itself. To the north of the station, the new Grand Front Osaka offers a similar mix of shopping, offices, hotels, and dining, with the new development made possible by moving an old freight yard. Sitting between Osaka station, and the neighbouring Umeda station is the Links Umeda building, a further multi-use complex. Umeda station is the hub of the Hankyu line, one of the many private lines that stretches out from the Osaka areas.

Within the Umeda area are sights that demonstrate modern Osaka’s exuberance. The Umeda Sky Building, northwest of Osaka Station, consists of two 40-story towers joined by a rooftop observatory complex. It provides a great location to look out over Osaka day or night for a view of the northern part of the city. It’s a popular spot for dating couples. For more night views, the Ferris wheel at the top of the HEP 5 shopping mall offers a great way to watch the sun go down. Beneath the streets of the city lies a spider web of underground shopping complexes, which are complemented above by covered shopping arcades. Doyamacho to the east of Umeda station is the city’s lively gay and lesbian district.

East of Umeda is the Tenma district of Osaka. Tenma is known for its food and traditional Osakan eateries and izakaya, particularly to the north of Tenma station. A 2-kilometer long covered shopping arcade, Tenjibashi-suji, travels through the area from Tenjin station to the Dojima river. Near the river, off of the arcade is Osaka Tenmangu Shrine, a shrine dating back to the 10th century, which is beloved by locals, and which is the heart of Osaka’s Tenjin Matsuri, one of the three great festivals in Japan. In July an exuberant celebration occurs where a mikoshi is carried throughout the neighbourhood. It’s a great area to explore for a taste of everyday Osaka. For those seeking a historic look back at everyday life in Osaka, the Osaka Museum of Housing and Living, which brings history to life with recreated stores, houses, and streets.

The sandbank of land between Dojima River and the Tosahori River is the island of Nakanoshima, home to Osaka’s City Hall. For those with an interest in ceramics, the Museum of Oriental Ceramics contains stellar examples not just from Japan but from throughout Asia. A traditional rose garden reflects some of the European influences in architecture and landscaping on Nakanoshima. The island is a pleasant place to stroll. In addition to the Osaka branch of the Bank of Japan, on the western side of the island art lovers will find the National Museum of Art, Osaka. Modern art in all forms, including photography and video, is the focus of the exhibitions held here. Families will find interactive exhibits and a planetarium at the Museum of Science, also located on the Western side of Nakanoshima.

Osaka’s most prominent landmark is its castle, standing proudly in the extensive parklands of Osaka Castle Park. Nearby lies the area where the former Naniwa Palace stood. The current Osaka Castle is a concrete replica. A castle was first built here by Toyotomi Hideyoshi but was burnt down by the Tokugawa Shogunate that took power to prevent Toyotomi’s followers from using the castle as a rallying point. In its place, in later years, the Tokugawa Shogunate built their own castle here which was completed in 1629. The main tower was destroyed by fire in 1665 and the entire structure was destroyed in 1868. The current replica was built in 1931 and houses a museum that brings to life the history of the castle. The moats and stone are a testament to the might of the Tokugawa Shoguns. For those who wish to learn more about Osaka’s history, stretching back to its Naniwa days, the nearby Museum of History reveals Osaka’s long past.

The Minami or Southern area of Osaka is now its modern heart, and it is a bustling area of the city near and around Namba station.

Dotonbori is a street running parallel to Dotonbori Canal. It is lined with a variety of casual restaurants, many of which serve into the small hours of the morning, or indeed on a 24-hour basis. The Osaka reputation for kuidaore is illustrated in the Dotonbori area. Some of the neon and signage that are well-loved landmarks of Osaka, such as the Glico man, and the moving crab sign of Kani Doraku, are found along the Ebisu bridge over the Dotonbori Canal. Cruises operate along the canal for those seeking a canal-eye view of Dotonbori. Those seeking kabuki will find performances at the Shochiku-za theater.

Those seeking more traditional Japanese restaurants will find these in Hozen-ji Yokocho. At its western end, you’ll find Hozen-ji Temple. The focus of devotion here is Fudo-Myo, and the statue is covered thick with moss kept vibrant by the water worshippers ladle over the statue. Nearby is the small Kamigata Ukiyo-e museum, featuring Kamigata woodblock prints that are typical of the Osaka era, featuring kabuki leading lights.

Running perpendicular to Dotonbori Canal and heading north is the Shinsaibashi shopping arcade, a covered arcade of shops extending 600 meters. Here you’ll find casual restaurants, shops with local delicacies, hotels, department stores, and clothing and brand shops. The shopping district itself has a 400-year history but most shops cater to the modern needs of residents and visitors.

East of Shinsaibashi is the Amerikamura district, where you’ll find some of Osaka’s more avant-garde fashion designers, boutique shops, second-hand shops, and cafes. You’ll find Osaka’s street fashion and up-to-the-minute styles. In the evening Amerikamura (also known as Amemura) is a popular nightlife district, with bars and small clubs.

Japan has a tradition of puppet theatre, bunraku, which originated with the 17th century Ningyo joruri tradition. Bunraku today is considered a UNESCO Intangible Cultural World Heritage. Performances feature a narrator, musical accompaniment, often by shamisen, and ornate puppets artfully articulated by masters clad in black. With their skill, the inanimate puppets take on a life of their own. The National Bunraku Theater is in the Minami district, east of Shinsaibashi and south of Dotonbori. Bunraku performances are targeted to adult audiences rather than the enjoyment of children and the tales performed are sometimes tragedies.

Kuromon Ichiba, Osaka’s well-loved market, lies near the National Bunraku Theatre. This market has its origins in feeding the people of Osaka and contains vendors of meat, seafood, fruits, and vegetables. The popularity of the market with visitors has led some stallholders to offer foods that appeal to those wanting instant gratification and who wish to snack while they explore. With 580 meters of the market to explore and 150 shops, there are plenty of opportunities to eat your way through the market. Or enjoy a meal in one of the restaurants that can be found in the market.

The Namba area brings together several different transportation links: JR, the Hanshin Line, the Kintetsu Line, the Nankai Line, and the Osaka Metro. The area caters to commuters and travelers of all sorts with many shopping complexes, Osaka’s flagship Takashimaya department store, and the relatively new Namba Parks development. Some of this shopping is more specialized. To the east and just south of the Namba Nankai station lies Denden town – Osaka’s answer to Akihabara, featuring electronics stores, games arcades, and anime shops. The Doguyasuji district serves the restaurant trade and is a great place to pick up a takoyaki pan, should you wish to make this Osaka specialty at home.

In the area nestled between the Minami district and the Tennoji area is Shin Sekai, or ‘New World’. It was initially built in the early 1900s following the National Industrial Exposition. Tsutenkaku Tower provided a focal point for the area and to the south was an amusement park inspired by Coney Island. The popularity of the area dwindled before the war and Tsutenkaku Tower and the area sustained damage during the war. The tower, the focal point of the area, was rebuilt in 1956. The area is awash with bright lights and beckoning restaurants, particularly those serving kushikatsu, and while the area does have a reputation for being a bit rough around the edges, it is certainly lively.

The Tennoji area of Osaka is one of the city’s oldest. The area has at its heart Shitennoji Temple, the oldest Buddhist temple in Japan. Orders to build the temple were given in the year 593 by Prince Shotoku. While the buildings in the current temple precincts post-date the founding of the temple, with most built from the 17th to the 20th century, there is a long spiritual tradition and much to discover here. The ‘Shi’ in Shitennoji refers to the four heavenly kings of Buddhism that protect the earth from evil. The Chushin Garan area, housing the main temple building and treasury provide some insights into the temple, and the Gokurakujodo gardens are one of a few remaining examples of a paradise garden design. A popular monthly flea market brings local visitors and travelers alike. On a sunny day, you’ll find basking turtles in most of the small water features of the precinct. The five-storied pagoda can be climbed for views over the precinct, and it enshrines Prince Shotoku as a Kannon. The temple is famous for its lively Doya Doya festival in January, where men dressed in loincloths in the winter cold scramble to get their hands on paper charms. The temple is also considered by many to be a power spot.

The Abeno Harukas building, also in the Tennoji area, is a recent addition to the area. You’ll be sure not to miss it, as at 300m tall, it is Japan’s largest building. The multi-use complex contains a train station, Japan’s largest department store, an art museum, a rooftop garden, restaurants, a hotel, and offices. The Harukas 300 observation deck offers views over the entirety of Osaka and into the distance. The Tennoji area is also home to Osaka’s Tennoji Zoo, and the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts.

In Southern Osaka, Sumiyoshi Taisha is the head shrine of over 2300 Sumiyoshi shrines in Japan. There has been a shrine at Sumiyoshi for 1800 years and it is commonly associated with maritime activities and travel. Accordingly, oversized ema plaques have been left by seafarers and ocean-going organizations over the years and can be found on the grounds of the shrine. The high arch of the Sorihasi bridge marks the entrance to the shrine. The architectural style of the shrine, Sumiyoshi Zukuri, is one of the oldest forms of shrine architecture in Japan – eschewing influences from outer Asia and reflecting a style with purely Japanese roots. The shrine is extremely popular for hatsumode, the tradition of making a shrine or temple visit early at the start of the new year. Millions will make their way to the shrine in the first few days of the new year. Throughout the year, the shrine is at the center of several Shinto festivities.

Osaka Bay area, in the city’s southwest, is the home bustling area of modern entertainment for the whole family. For those seeking theme park adventure, the Japanese outpost of Universal Studios is located on the bay. A complex of accommodations and entertainments lie in the area immediate to the theme park. Known commonly as USJ, the theme park is often busy with long queues for the most in-demand rides. It is popular with domestic and international visitors alike. A ‘Super Nintendo World’ has opened within the park, for those with an interest in gaming. Younger visitors are accommodated with Sesame Street-themed attractions and gentle rides. Meanwhile, the pre-teen set can often be found in the Harry Potter-themed rides and attractions.

On the bay, you’ll also find Osaka’s magnificent aquarium, Kaiyukan. The theme of the Aquarium is the Pacific ocean’s ‘ring of fire’ and draws on locations from around the Pacific rim. Japanese otters, spider crabs from the depth of the arctic circle, creatures from off the Ecuadorian rainforest, and Antarctic penguins all feature in the aquarium. Whale sharks to jellyfish, rays to octopi – all can be found at Kaiyukan. For those who wish to take in the ocean from the air, the Tempozan Ferris Wheel at Tempozan marketplace also offers views over Osaka, and a full turn around the wheel takes 17 minutes due to its great height. Further onward, the port of Osaka services ferries to Shikoku and Kyushu. Some convention centers also cluster at the port.

The city of Sakai lies south of Osaka. Sakai is home to several ancient keyhole-shaped kofun or tumuli. The kofun were built in the 3rd to 7th century and are feats of engineering. Though they do not contain buildings, it is thought that it took at least 15 years and 2000 workers to create the sites. The tumulus area can not be entered, but there are shrines and temples around the site dedicated to those buried within. Technology however allows us an approximation of what the kofun are like, and a virtual reality experience at the Sakai city museum seeks to provide visitors with a taste of what the kofun are like. The tumulus is encompassed by three moats, making it clear even centuries later that these kofun were to remain inaccessible.

The Mozu Furuichi tumuli are home to 49 tombs and several iron age archaeological finds have been made in the tomb area, including weaponry, and terracotta figures called Haniwa. The purpose of these ancient Haniwa are mysterious but are thought to designate a sacred space. These finds come from outside the kofun themselves as archaeologists may not enter or disturb the kofun. The largest of the keyhole tumuli at Mozu is thought to contain the grave of Emperor Nintoku. In all at Mozu, there are 44 tombs spread across a 4 km square area. Emperors Richu and Hanzei are also buried in Kofun in the Sakai area. The kofun were designated UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 2019.

Sakai is also famous for its metalworking traditions, and swords, knives, scissors, and the like are still crafted here using ancient methods. The town’s Hamono Museum chronicles the knifemaking tradition in Sakai. Chefs from the world over seek out the hand-crafted knives made in Sakai that are considered to be exceptionally strong and sharp. Mizuno Tarenjyo continues to make swords and knives using an open flame and bellows to control the heat needed to soften, reshape, and forge strong steel blades. Some knifemakers offer visitors the chance to learn how to properly sharpen a knife and to learn other parts of the knifemaking process, such as fitting handles to the steel blades. Metalworking in the area was not limited to blade-making. As blades gave way to firearms in military technology, Sakai became the leading region in Japan for firearm production. Most of the historic gunsmith buildings are no more, but the 17th-century residence and shop of Sekiemon Inoue remain and can be visited for insights into the lives of the gunsmiths of the Edo period. The building, dating from the late 1600s, is one of the oldest examples of machiya construction in Japan in original condition. The surrounding Kitahatagocho region of Sakai still retains a feel of those times. Still, the craftsmen of Sakai continue to reinvent themselves and reorient their production to progress. Guns are no longer produced in Sakai, and at Sasuke, the current master is the 22nd generation to be engaged in metalwork. However, while the first 17 generations produced guns, the 5 most recent generations shifted production to knives and scissors.

The area also has a long history. The Mozu Hachimangu shrine is said to have been built during the 6th century. A tree on the grounds of the shrine is thought to be up to 800 years old. The shrine still preserves the old tradition of conducting a moon-viewing festival during August of the lunar calendar to pray for a rich harvest. The Kotani family was one of the dominant families in the area, and Kotani Castle continues to chronicle the history of the clan and exhibits various works of art and archaeological finds. The castle itself is now in ruins, the main family houses and outbuildings can still be visited today. The Otani that made the castle their home were members of the Taira clan.

The famous tea master, Sen no Rikyu, who originated the Senke school of tea ceremony, was born in the Imaichi area of Sekai city. The site of his house is commemorated here, and though the house itself is gone, the well associated with it remains.

South of Sakai is Kishiwada, a city of Osaka Prefecture that is famous for its lively, and downright dangerous Kishiwada Danjiri festival. During the festival, famous throughout Japan and typically attended by half a million people, 35 beautifully carved floats are run throughout the city at high speed. The floats are fearlessly navigated by the Daiku-Gata, who balance on top of the roof of each float, directing progress while it whips through the city. For those who visit Kishiwada outside of festival time, there is a Kishiwada Danjiri Museum that brings the festival to life and places it within the context of local life in the community over the previous 300 years. Kishiwada Castle also offers an opportunity to enjoy traditional Japan juxtaposed with modern Japan. Its Stone Garden was designed by architect and designer Mirei Shigemori.

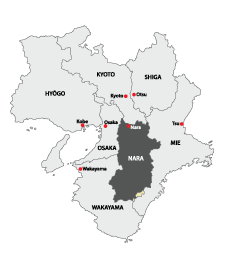

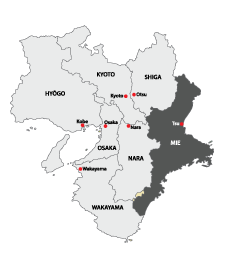

Shiga Prefecture

Shiga prefecture lies in eastern Kansai and is bordered to the north by Fukui prefecture, to the east by Gifu prefecture, to the south by Mie prefecture, and by Kyoto prefecture to the west. The prefecture is home to Biwako, or Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan. Shiga sits at the crossroads of Eastern and Western Japan, and settlement here dates back to the 7th century with Emperor Tenji establishing a palace at Otsu and making it temporarily Japan’s capital. With such a long history of settlement and an important location on the island of Honshu, the prefecture is home to many sights of historical significance. Many visitors pass through Shiga prefecture on the shinkansen or bullet train, as it makes its way to nearby Kyoto, but don’t stop, preferring instead to devote their time to Japan’s more enduring ancient capital. The hidden beauty of this region is held quietly by those living in Kansai.

Shiga prefecture lies in eastern Kansai and is bordered to the north by Fukui prefecture, to the east by Gifu prefecture, to the south by Mie prefecture, and by Kyoto prefecture to the west. The prefecture is home to Biwako, or Lake Biwa, the largest lake in Japan. Shiga sits at the crossroads of Eastern and Western Japan, and settlement here dates back to the 7th century with Emperor Tenji establishing a palace at Otsu and making it temporarily Japan’s capital. With such a long history of settlement and an important location on the island of Honshu, the prefecture is home to many sights of historical significance. Many visitors pass through Shiga prefecture on the shinkansen or bullet train, as it makes its way to nearby Kyoto, but don’t stop, preferring instead to devote their time to Japan’s more enduring ancient capital. The hidden beauty of this region is held quietly by those living in Kansai.

Lake Biwa is undeniably the most prominent feature of the area, taking up a sixth of the prefecture’s size. Farmland, primarily rice-producing, takes up another sixth of the land. Most of Shiga’s notable sights are located in the area around Lake Biwa. The lake was formed 4-6 million years ago, making it one of the earth’s oldest lakes, and measures 80 km from north to south, and at its widest point, measures 24 km. It has been categorized as a UNESCO Ramsar wetland and is home to numerous local species endemic to the area. In the centuries past, the lake was a means for moving goods over distance and was key to trade in the region. The waters of Lake Biwa are revered by both the Shinto and Buddhist faiths, associated with purification and cleansing, as well as protection.

Otsu, the capital of Shiga prefecture, sits at the southern end of the lake, an easy 10-minute train journey from Kyoto. Lake cruises depart from Otsu, and hotels take advantage of the beautiful backdrop provided by the lake for wedding functions. If you can overcome the seeming disconnect to place, you can even enjoy a paddle steamer cruise on the lake that might make you think you are cruising the Mississippi instead of Lake Biwa. Given the proximity to Kyoto, and by extension to Osaka, it is not surprising that there are also facilities that cater to those coming to Lake Biwa for recreation. There are watersports companies, serving those looking to kayak, canoe, sail, or windsurf on the lake and for those who wish to keep the lake in the background, there are also bicycle rental companies. Stand-up paddling, and of course, swimming, are great summer options. Omi Maiko beach, on the western shore of the lake, is a great location for the latter.

Mt. Hiei, straddling both Kyoto and Shiga prefectures, and located between Kyoto and Lake Biwa, is considered to be a sacred mountain and it features within the Japanese creation myths of the Shinto tradition. This reverence was also felt in the recently arrived Buddhist faith, and Enryaku-ji Temple was founded in 788 and is the home of the Tendai sect of Buddhism. Enryaku-ji is known for its ‘marathon monks’ or gojya that express their devotion through physical exertion beyond most. They’ve earned this moniker from the practice of kaihogyo, a 1,000-day test of endurance and strength that includes refraining from taking food or drink for many days at a time, making pilgrimages to scores of sites of significance on the mountain, and running 84 km for 100 days in a row. It is not a devotion for the weak and many performing kaihogyo over the centuries have not come out of their challenge alive. From 1835 there have only been 46 gojya. The founders of several other Buddhist sects in Japan studied here before diverging from the Tendai path.

The marathon monks are not the only well-known people associated with Enryaku-ji, though not without devastating impact to the temple complex. During the warring states period in the late 16th century, the temple and its physically powerful and influential monks were considered a threat to political power, and as was commonplace throughout Japanese history, the tension between sacred and secular power led to conflict. Oda Nobunaga attacked Mt. Hiei and razed all but one of the temple buildings. Most of those standing today were built in the Edo period. For the purists and active travelers, the most satisfying means to reach Enryaku ji temple is on foot, but for many more, the temple is reached by funicular.

In the inland area to the west of Lake Biwa, Biwako Valley is a ski and snowboarding resort of modest height that perhaps is best enjoyed in the green season. There is a zipline for thrills, and a visit to the Biwako Terrace is a must for those that wish to take in an expansive view of the lake. It is possible to access the Biwako terrace by the Zekkei ropeway.

Both captivatingly beautiful and ancient, the Shirahige shrine lies on the western shore of Lake Biwa in the northern town of Takashima. The shrine has been an ancient sacred spot for nearly 2000 years and is marked by more recent buildings. Perhaps it is not surprising given the age of the shrine that the deity enshrined here, Sarutahiko-no-Mikoto, is associated with longevity. The shrine’s torii gate standing in the waters of Lake Biwa is a photographer’s dream. Closer to Otsu the Ukimido or floating main hall of Mangetsu-ji temple sits on the lake and can be accessed by a promenade over the water. The current structure is a 20th-century reconstruction of the original, but the temple itself dates back to the 8th century. The Ukimido houses 1000 Buddha statues.

Southeast of the southernmost point of Lake Biwa lies Miho, Shigaraki, and Koka. Miho is home to the Miho Museum, built by renowned architect I.M. Pei, who also built the Louvre’s modern-day glass pyramid. There are echoes of that pyramid here. Most of the museum lies underground and it blends into the background. The collection here consists primarily of Japanese art and artifacts. Shigaraki is a centre for pottery and is one of the six old pottery towns of Japan. It has also carved out quite a niche in creating large ceramic tanuki figures. This raccoon dog is known to enjoy a drink and is known in folklore as a shapeshifter. Tanuki figurines are often found at establishments serving alcohol. Koka is a town that is dedicated to the art of stealth and is home to a Ninja village and home of a well-known ninja clan. The house retains secret passageways, trap doors, and security measures that protected the ninja. The ninja village also has elements of these secret methods on a less grand scale.

The eastern shores of Lake Biwa are home to lakefront towns that retain some of their historic feel. Omi-Hachiman, one of the post towns of the Nakasendo Trail, was a hub for the famed Omi merchants. The town has a picturesque canal district lined with Edo period merchant homes and weeping willows. In warmer months you can travel by boat through the canals. The high living of the local merchants can be explored in the Shin-machi Dori street of the town, and in particular the Nishikawa Residence. The local museum also provides insights into the history of the town. For a view of the lake, a trip by ropeway up Mt Hachiman to the site where a castle once stood.